Get a bunch of actuaries together (particularly life insurance actuaries) and sooner or later we will start talking about pandemics. Fortunately, our experiences are almost entirely theoretical. We’ve lived through AIDS (for the life insurance actuary, a very slow-moving pandemic, where the challenge was more about underwriting than claims and capital) and SARS (which, from Australia, was more economic than insurance related) and the 2009 Swine Flu, which was (from an insurance industry perspective) almost entirely about PR.

But one day, our industry will be called upon to deal with a real pandemic, something like the “Spanish Flu” pandemic of 1918 which I blogged about here.

So where does Ebola fit on this continuum? Who tells us that although Ebola is a very scary disease if you get it, it isn’t highly infections.

The Ebola virus is highly contagious but only under very specific conditions involving close contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person or corpse. Most infections have been linked to traditional funeral practices or the unprotected care, in homes or health facilities, of an infected person showing symptoms.

The best article I have seen is this one from the Economist which talks soberly about how bad it really is.

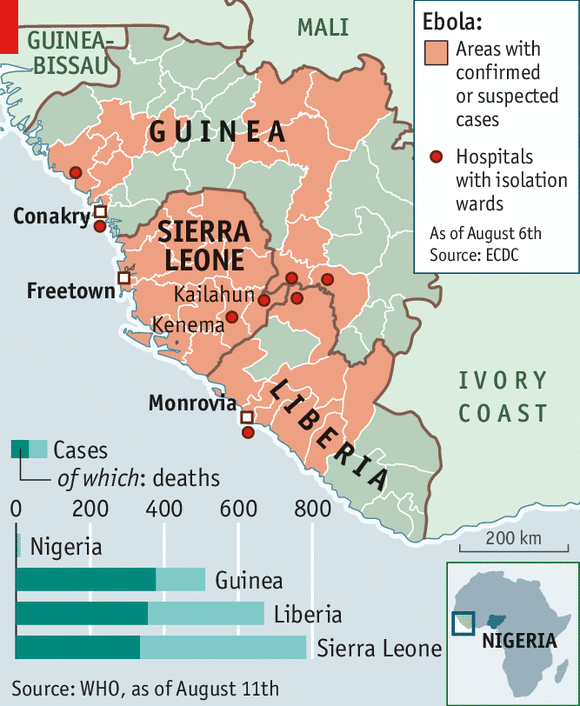

It has been more than nine months since Ebola claimed a two-year-old boy in a village in Guinea—“patient zero” in the current outbreak. But rather than petering out, the virus seems to be ramping up. It has infected nearly 2,000 people in west Africa. Over 1,000 of them have died, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). That is probably an underestimate. Some families, distrustful of outsiders and authorities, are concealing sick relatives.

Compared with other infectious diseases in Africa, Ebola is a small-scale killer. But the virus is devastating for the region nonetheless.

The frightful nature of the disease, which can cause vomiting, diarrhoea and uncontrollable bleeding, and the lack of a cure have led to panic and fear.

And then this article (also from the Economist) talks about the economic impacts, which are likely to be more severe than the direct impacts from this outbreak:

The economic costs of epidemics are often out of proportion to their death toll. The outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 is estimated to have caused over $50 billion-worth of damage to the global economy, despite infecting only about 8,000 people and causing fewer than 800 deaths.

Governments walk a fine line between limiting the spread of a disease and causing needless disruption. Panic is avoided not just by combating an epidemic, but by being seen to do so. Transparency is important. By disclosing the extent of an outbreak, governments limit the spread of rumours and encourage an appropriate response from business and the public.

IHS, a risk consultancy, thinks that if the virus spreads further more mining operations will be suspended, with potential declarations of force majeure. Investors have taken note: share prices for heavily exposed companies have plunged since the epidemic began.

In some ways, if the indirect economic impacts are the worst Africa (and the world) experiences, we will be pretty lucky. They aren’t great (I was part of a company with significant operations in HK during SARS, and I remember pretty severe impacts then), but they are better than the alternative of a serious pandemic.

While Ebola seems a very scary disease, at the moment the parameters are manageable. If you’ve played Plague Inc, you know that the key parameters for a pandemic are infectiousness and deadliness. For maximum effectiveness, your disease needs to start by being not very deadly, and very infectious. Fortunately for everyone who isn’t in the directly affected countries, Ebola is the opposite. It is hard to catch (the Economist again):

Each Ebola victim usually infects just one or two others, whereas a case of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), first reported in Asia in 2003, generates three more.

and it tends to kill people quickly, which again, means it is less likely to spread. But its fatality rate of well over 50% is terrifying. So while wikipedia’s latest statistics are 1,145 deaths from 2,127 cases, it is probably not something you need to panic about unless you actually live in the rural parts of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone that are currently affected.

This article from the Lincolnshire Echo (a paper desperately trying to find local relevance) is probably at least as relevant for Australia:

No-one in Lincolnshire has so far had to be tested for Ebola, officials have revealed.

Bosses at United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust say they have so far not been informed of any tests taking place in the county.

If you’re taking precautions, take them against the current winter flu, which will probably kill more people in total (it killed 1600 Australians in 2009).

The Spanish Flu (a strain of the H1N1 virus) is to date the most deadly pandemic. Unfortnuately a substantial number of people actually died due to excessive overdoses of aspirin. The swine flu was also a strain of the H1N1 virus.

An “effective” pandemic is one where being healthy is actually a disadvantage – hence the reason for higher mortality at younger ages. This can only be caused by a malfunction of the immune system.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cytokine_storm